It never rains but it pours

Coronavirus threatens to complicate response to potential spring flooding

Local residents join to hold back the Mississippi River with sandbag banks and water pumps in Savanna last spring. (Facebook/Mayor Chris Lain)

By Ted Cox

As the nation struggles to get a handle on the new coronavirus pandemic, it threatens to complicate another familiar, almost annual public scourge: spring flooding.

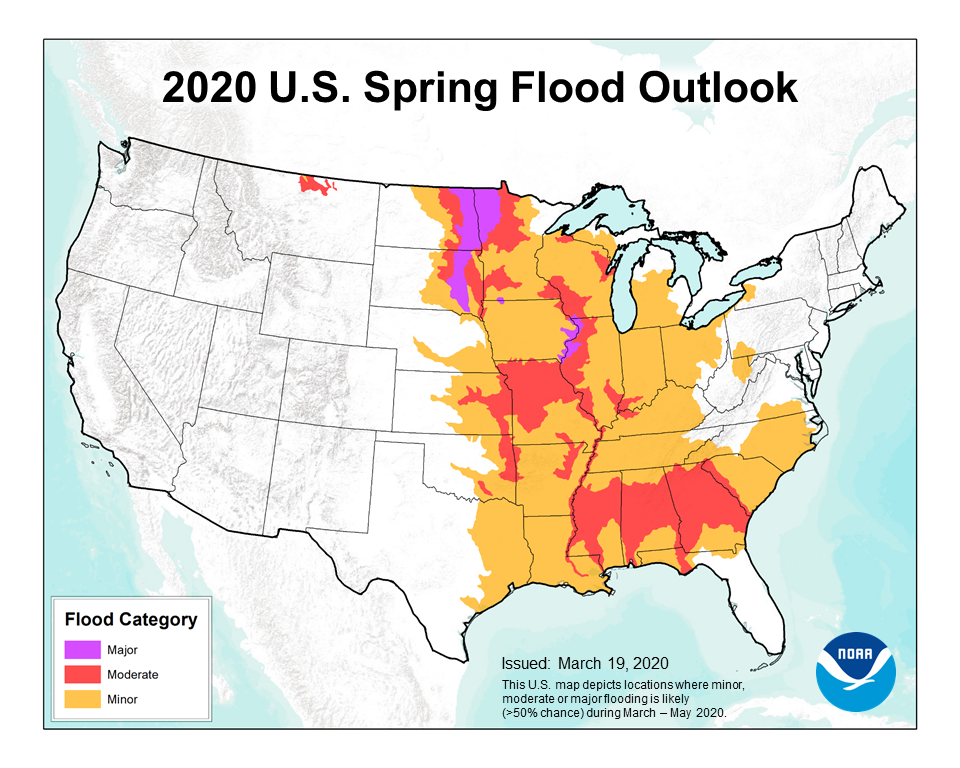

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released its spring flood projections last week, declaring 23 states at risk of moderate to severe flooding, including Illinois. The NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center forecast “above-average temperatures across the country this spring, as well as above-average precipitation in the central and eastern United States.”

The federal agency went into detail, explaining that “ongoing rainfall, highly saturated soil and an enhanced likelihood for above-normal precipitation this spring contribute to the increased chances for flooding across the central and southeastern United States. A risk of minor flooding exists across one-third of the country.

“The greatest risk for major and moderate flood conditions includes the upper and middle Mississippi River basins, the Missouri River basin and the Red River of the North. Moderate flooding is anticipated in the Ohio, Cumberland, Tennessee, and Missouri River basins, as well as the lower Mississippi River basin and its tributaries.” It went on to predict: “Above-average precipitation is favored from the northern Plains, southward through the lower Mississippi Valley across to the East Coast.”

A map the agency released on the “2020 U.S. Spring Flood Outlook” shows the entire western Illinois border with the Mississippi River at moderate risk of flooding, including inland from where the Illinois River joins it along with the Missouri River just north and south of Alton.

(NOAA)

But at major risk of flooding is the northwest corner of the state, which saw extensive flooding last spring, as in Savanna, where they fought for weeks to keep the Mississippi from filling the town.

The idea of all-hands-on-deck sandbagging is all but unthinkable in the midst of the current COVID-19 outbreak, with its demands for social distancing to stem the spread of the disease, but towns and cities along the Mississippi might have to find ways to adapt.

State Climatologist Trent Ford reported a relatively normal February on precipitation and a reasonable winter snowpack from the winter in an interview this week with RFD Radio. But he warned of a heightened flood risk across southern Illinois given more recent heavy rains in March of 5 inches or more in Jefferson and Clay counties. He cautioned against flooding along the Ohio River along the southeast Illinois border as it makes it way to the confluence with the Mississippi at Cairo.

“February ended up being pretty close to our 30-year normal as far as temperature and precipitation across pretty much all of the state,” Ford said. “March hasn’t been that way, especially for the southern and southeastern quadrant of the state.”

Ford warned in late February that much of the soil in southern and central Illinois was at a saturation point, extending west all the way to the Dakotas. He repeated that warning for southern Illinois, where those 5-inch rainfalls amount to double the usual precipitation for March.

“Considering the amount of precipitation that has fallen southeast of there in Kentucky and across the Tennessee Valley, that’s really an issue and has resulted in some long-term flooding along the Ohio River,” he said. “The hydrological indicators for spring flooding are the amount of precipitation we get, soil moisture, and snowpack in the upper Midwest. The snowpack hasn’t been too bad compared to last year — it’s been melting relatively slowly — but those soils across southern Illinois continue to be at or near saturation so there’s really no capacity in our system right now to take in much additional moisture, especially in the southern half of the state.”

Farmers across the state and residents along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers will be looking to the skies to make sure rains don’t make the terrible outbreak of COVID-19 even worse.