Things We Read: 'Black Hawk: An Autobiography'

Sauk tribal leader rivals Abe Lincoln as the state’s most tragic figure

The statute of Black Hawk — mislabeled, of course — at the State Historic Site named in his honor in Rock Island. (One Illinois/Ted Cox)

By Ted Cox

As One Illinois closes in on the end of its first calendar year, we’re revisiting some of the places, events, and stories that have most captivated us in our journeys crisscrossing the state.

And of all the stories in Illinois history, the one that is probably the most well known on the surface, yet least known in any kind of depth, is that of Black Hawk, the Sauk warrior.

Black Hawk is one of the truly tragic figures in state history. Never actually a “chief,” he led a confrontational faction of his tribe in the face of settlers in 1832, and he appears to have conducted himself throughout his life with a rigid consistency, true to the Sauk code of honor and conduct. Yet in the end he was left defeated and humiliated before dying.

Black Hawk, also known by the tribal name Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, is believed to have been born in 1767 in the village of Saukenuk, on the Rock River near its confluence with the Mississippi, just below what is now the Black Hawk State Historic Site in Rock Island.

That’s where we picked up a copy of “Black Hawk: An Autobiography,” an 1833 text as told to an iffy translator and printed by a newspaper publisher with his own motives, fully edited and reprinted in 1955 by University of Illinois Press Editor Donald Jackson, and reprinted again in the ‘80s.

As acknowledged by Jackson in his original introduction, the subtitle "An Autobiography” is key, in that some have questioned its authenticity. There is clearly some license taken by the newspaper editor and translator who originally took the story down shortly after the so-called Black Hawk War and a less-than-triumphant ensuing tour through the East, including a meeting with President Andrew Jackson. Yet Black Hawk's story of Sauk life and the mistreatment of his tribe at the hands of white settlers comes through and rings true.

Saukenuk was actually burned by U.S. forces in 1780 in what is commonly considered the westernmost conflagration of the Revolutionary War. They were trying to punish tribes they believed had aided the British. Black Hawk makes no reference to that in his autobiography, but does address the War of 1812, in which it should be no surprise the Sauk sided with the British. Also influential in that decision was that in 1804 Sauk representatives were intoxicated and bamboozled into signing a treaty in St. Louis giving away tribal lands east of the Mississippi — which would only later figure in what would be termed the Black Hawk War.

“I had not discovered one good trait in the character of the Americans that had come to the country,” Black Hawk recalled in his life story. “They made fair promises but never fulfilled them. Whilst the British made but few — but we could always rely on their word.”

Black Hawk writes of skirmishes with other tribes as the Sauk protected their summer home of Saukenuk, where the women annually grew a crop of corn and other vegetables, and their winter hunting grounds across the Mississippi in Iowa. That for the most part peaceful society is depicted in a lovely set of dioramas at the Black Hawk State Historic Site, although it should also be noted that Black Hawk stated in his autobiography that he put together a formidable fighting force: “A band of warriors more brave, skillful and efficient than mine, could not be found.”

Black Hawk speaks eloquently of tribal origin stories, such as how the Sauk came to plant corn, and about the tribe’s sense of community and sharing. They were confounded by the duplicity (and the Christianity) of white settlers: “We can only judge of what is proper and right by our standard of right and wrong, which differs widely from the whites, if I have been correctly informed. The whites may do bad all their lives, and then, if they are sorry for it when about to die, all is well! But with us it is different: we must continue throughout our lives to do what we conceive to be good. If we have corn and meat, and know of a family that have none, we divide with them. If we have more blankets than sufficient, and others have not enough, we must give to them that want.”

Meanwhile, the Potawatomi to the northeast were being swindled out of what would become Chicago.

The very concept of property is foreign to the Sauk: “My reason teaches me that land cannot be sold. The Great Spirit gave it to his children to live upon, and cultivate, as far as is necessary for their subsistence; and so long as they cultivate it, they have the right to the soil — but if they voluntarily leave it, then other people have a right to settle upon it. Nothing can be sold, but such things as can be carried away.”

After being inaugurated in 1829, President Jackson initiated a policy to remove all American tribes west of the Mississippi. At the same time, George Davenport, namesake of the Iowa town in the Quad Cities, was buying up the land at Saukenuk. The following year, a tribal agent named Thomas Forsyth was replaced, and a more confrontational U.S. general took charge of the area, egged on by Illinois Gov. John Reynolds, who adopted President Jackson’s policies.

"Then we were as happy as the buffalo on the plains," Black Hawk says of the time before the settlers' arrival, "but now, we are as miserable as the hungry, howling wolf in the prairie!"

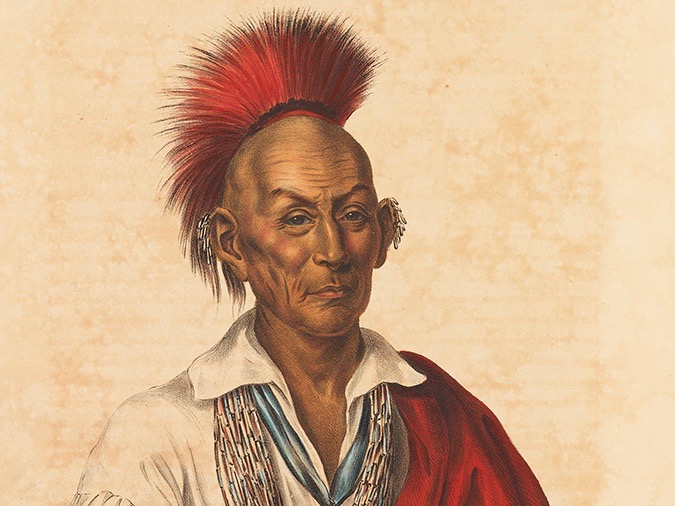

Black Hawk as portrayed in a print performed during his lifetime.

Black Hawk tells of the tribe returning from their winter hunting grounds one spring to find white settlers occupying Saukenuk, and planting on their very cornfields. Loquacious, conciliatory Sauk leader Keokuk advocated moving across the Mississppi, but Black Hawk did not, and in the belief that he might rendezvous with British forces he led a ragtag band of an estimated 500 warriors and 600 women, children, and the aged back across the Mississippi in 1832. Keep in mind, Black Hawk himself would have been 65.

He insisted his initial tactics bordered on what would now be considered passive resistance: “I directed my village crier to proclaim, that my orders were, in the event of the war chief coming to the village to remove us, that not a gun should be fired, nor any resistance offered. That if he determined to fight, for them to remain quietly in their lodges, and let him kill them if he chose.”

But things didn’t work out that way. Black Hawk’s “British Band” wandered at first in search of what turned out to be apocryphal British forces and other tribes they believed might ally with them. Confronted at Stillman’s Run in north-central Illinois by U.S. forces, Black Hawk later insisted he sent a peace party under a white flag to negotiate for a uneventful return across the Mississippi, but the peace party was captured and Sauk warriors observing from a distance were fired upon. Black Hawk turned and fought and routed the militia with a raid at dusk.

What followed was a series of hit-and-run missions and other confrontations as the band meandered through northern Illinois and into Wisconsin. The “campaign,” if it could be called that, was largely a fiasco on both sides. Abraham Lincoln joined a militia that was soon sent back home as the U.S. Army was placed in charge. Brigadier Gen. Henry Atkinson dallied waiting for reinforcements from the East, delayed by an outbreak of cholera. Black Hawk’s British Band wandered farther north in ever-decreasing numbers. Caught by militia in the Battle of Washington Heights in Wisconsin, Black Hawk believed them defeated and that they would be granted passage back across the Mississippi, while he continued on to meet up with the Chippewa tribe. Instead, the 500 remaining members of the band, an estimated 150 of them warriors, were cut off by a U.S. warship at the mouth of the Bad Axe River.

The Battle of Bad Axe is now more commonly called the Bad Axe Massacre.

“Early in the morning a party of whites, being in advance of the army, came upon our people, who were attempting to cross the Mississippi,” Black Hawk states. “They tried to give themselves up — the whites paid no attention to their entreaties — but commenced slaughtering them! In a little while the whole army arrived. Our braves, but few in number, finding that the enemy paid no regard to age or sex, and seeing that they were murdering helpless women and little children, determined to fight until they were killed!”

Black Hawk was soon captured, held for a time in prisons, and then brought east, basically to be paraded before citizens to calm them about how the leader of the “Black Hawk War” was now a docile tribesman forced to confront the powerful civilization that was sure to overrun his people. “The tomahawk is buried forever!” Black Hawk said. He met President Jackson, albeit briefly, and was taken on to Baltimore and New York City before being brought home. Along the way he saw fireworks for the first time, “which was quite an agreeable entertainment — but to the whites who witnessed it, less magnificent than the sight of one of our large prairies would be when on fire.”

He dictated his autobiography, published in 1833, and was returned to the Sauk tribe in Iowa, living humbly under the leadership of Keokuk, whom he had always regarded as a coward. He died five years later.

“Black Hawk was never a great Indian statesman like Tecumseh or a persuasive orator like Keokuk,” Donald Jackson writes in his introduction. “He was not a hereditary chief or a medicine man. He was only a stubborn warrior brooding upon the certainty that his people must fight to survive.”

Here’s Zachary Sigelko’s video from our visit to Rock Island early this year.